I don’t remember exactly when I started hearing about Astro, one of the latest static site generators to help tackle the problem of building sites with less Javascript. The problem is one we’re all familiar with - how can I build a static site (in my case, my personal site) using the languages and tools I know best, while performing at its best? After migrating from Wordpress, I first tried Gatsby, then Gridsome, and most recently Nuxt. All of these are excellent tools, and I highly recommend them. But one thing that is the same across all of them is that they are tied to their specific framework (React or Vue).

Astro does away with that, and it’s one of the things that really drew me to the framework. From their site:

It’s time to accept that the framework wars won’t have a winner — that’s why Astro lets you use any framework you want (or none at all). And if most sites only have islands of interactivity, shouldn’t our tools optimize for that? We’re not the first to ask the question, but we might be the first with an answer for every framework.

This caught my interest. The idea of “framework wars” having a winner never made sense to me. None of these tools - React, Vue, Svelte, Angular - need to be the overall winner to make developers productive. Having a winner at all would mean that innovation is stalled, at best. The fact that Astro allows you to utilize whichever framework is most comfortable means that it can adjust to whatever change comes in the future, and focus more on what it does best: building static assets.

And so, as one does, I decided to rewrite my personal site from Nuxt to Astro.

Performance Woes

I should say, before going too much further, that I love Nuxt as a framework. I think it’s an amazing tool, and I realize that, as I write this, we are days away from the release of Nuxt 3’s public beta.

That said, I’ve been running a number of sites with Nuxt in static site mode, and each of them has some odd quirks that I’ve never been able to fully work out. One site, a single page in the truest sense with only a bit of reactivity, was constantly reporting Typescript errors in VS Code. This was because the VS Code plugins (either Vetur or Volar) did not recognize that Nuxt’s asyncData method returned state to the Vue object. This is not Nuxt’s fault, but it made things annoying.

A second site (which is purely static assets, almost no JS interaction in the browser) had an issue that when code was updated, any content fetched with Nuxt’s Content module would be missing after the hot module reload finished. I found a workaround, and it’s not a huge deal, but it’s annoying.

My personal site uses data from multiple sources, including Github and a few podcasts RSS feeds. Using Nuxt, I was doing more data fetching on render than I wanted. This hadn’t been an issue with either Gatsby or Gridsome, and I expect that if I had explored buildModules more closely I could have found a solution. As it was, some pages had to fetch content on the client, and when that content is split between multiple endpoints, it made things slow.

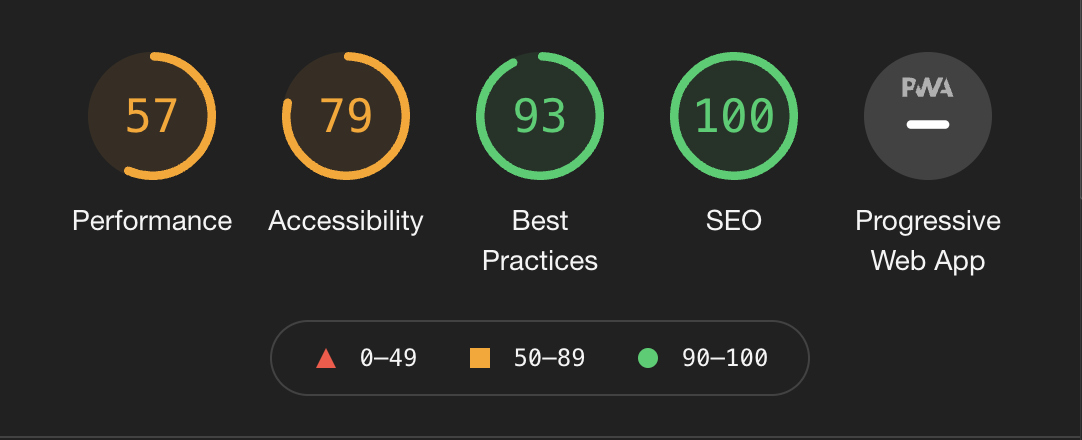

All of these sites, from the smallest to the largest, had one unifying issue: Lighthouse performance scores were never great. Below are my Lighthouse scores for this site before migrating from Nuxt:

This was done on my home page, on a fresh instance of Chrome with no plugins installed, in order to get the closest to a clean reading. The home page is loading a handful of images (language icons, my profile image), my latest blog post, and a few SVGs for social icons courtesy of Font Awesome. Data was also being fetched from Github’s GraphQL API to get my profile’s description, pinned repositories, and a few other details.

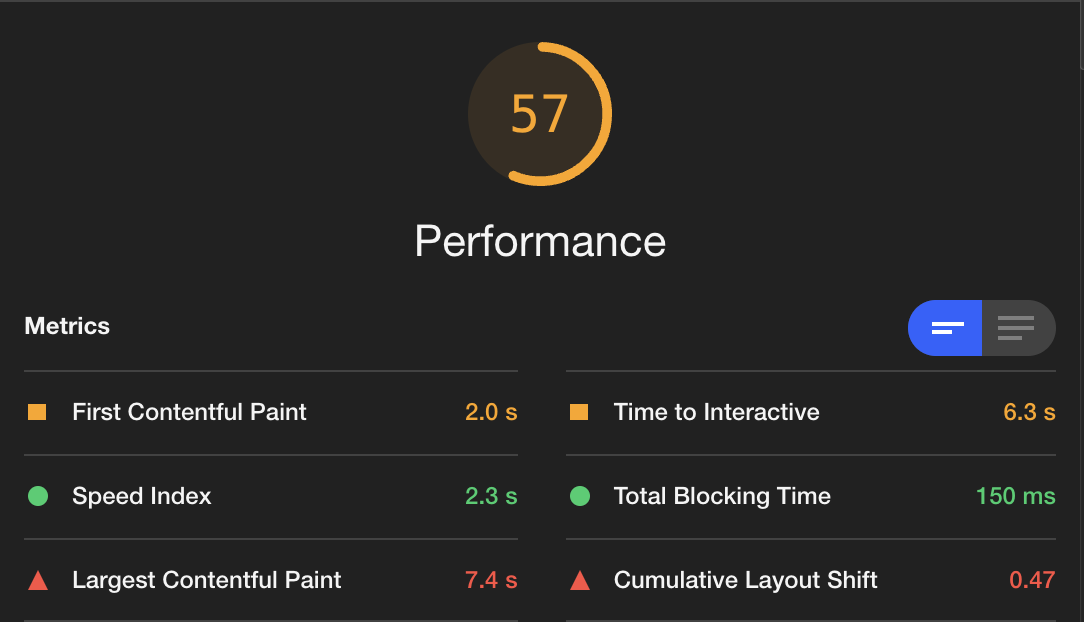

Here’s the breakdown of the performance score:

Of these scores, the Largest Contentful Paint and Time to Interactive stood out to me the most. This is a mostly static page, with a number of links and one button (to toggle dark mode). Why was Nuxt taking so long to be interactive?

Looking at my Network requests, it looks to me like Nuxt is mostly fetching Javascript, and then spending its time executing it. I made a few notes to see what I was looking at. On a typical page load, I had:

- 37 unique requests

- 6.7MB of resources loaded (including images)

- Load time: 2.5s

What could I do to cut down on all of this data fetching and Javascript execution?

Time for Less Javascript

This is where Astro caught my attention. On their home page, they say:

For a technology built on top of three different languages, the modern web seems to focus an awful lot on JavaScript. We don’t think it has to—and that’s certainly not a revolutionary concept.

We’ll eagerly jump at the chance to sing JavaScript’s praises, but HTML and CSS are pretty great too. There aren’t enough modern tools which reflect that, which is why we’re building Astro.

Astro is a framework that is focused primarily on fetching your data from whichever source or sources you use, injecting it into an HTML template, and building static assets from it. While Astro is built on Javascript, it doesn’t focus on sending Javascript to the client. Any functionality you want can still be brought in, whether that’s vanilla JS, React, Vue, or something else.

This way of building a static site feels very comfortable and familiar to me. I started web development in HTML, CSS, and PHP, and avoided Javascript at all costs for many years (both before and after jQuery came onto the scene). Rendering HTML and CSS to the client is what I did, with some logic involved to perform simple tasks like displaying a list of elements or fetching data from a database. Using Astro, it’s basically the same thing, just using Javascript instead of PHP.

Here’s an example of my main blog page, which renders a list of blog posts. Astro uses a unique syntax that combines the look and feel of Markdown, JSX, and standard HTML. All build time Javascript is handled in a ‘frontmatter’-like block at the top of the file, and the static template is built below that.

---

// Import components

import BaseLayout from '../layouts/BaseLayout.astro'

import BlogPostPreview from '../components/BlogPostPreview.astro';

// Fetch posts

const allPosts = Astro.fetchContent('./blog/*.md')

.filter(post =>

new Date(post.date) <= new Date()

)

.sort((a, b) =>

new Date(b.date).valueOf() - new Date(a.date).valueOf()

);

// Render to HTML

---

<BaseLayout>

<div class="flex flex-col lg:flex-row flex-wrap">

{allPosts.map(post => (

<div class="w-full lg:w-1/2 xl:w-1/3 p-4">

<BlogPostPreview item={post} />

</div>

))}

</div>

</BaseLayout>This may look familiar to someone who has used React before, with just a few oddities (no key on the mapped JSX? Extra dashes between the head and the return?), but it’s important to remember that the result of this is pure HTML. No Javascript will ever be parsed on the client from this snippet. These components are all written with Astro’s unique syntax, but the same is true when using React, Vue, or anything else: only static HTML and CSS would result from rendering this page.

But what if you want to load some Javascript? What if you need some client side interaction?

Partial Hydration

Astro promotes the concept of Partial Hydration. From Astro’s documentation:

Astro generates every website with zero client-side JavaScript, by default. Use any frontend UI component that you’d like (React, Svelte, Vue, etc.) and Astro will automatically render it to HTML at build-time and strip away all JavaScript. This keeps every site fast by default.

But sometimes, client-side JavaScript is required. This guide shows how interactive components work in Astro using a technique called partial hydration.

Most sites do not need to be fully controlled by Javascript. This concept of partial hydration leans into that. Using my personal site as an example, the only dynamic portion of the site is toggling dark mode. In the Nuxt version of the site, I was reliant on the Nuxt runtime to toggle light and dark mode. To be frank, that’s overkill for a static site. I shouldn’t have to render an entire SPA just to toggle dark mode, right?

On their page about partial hydration, the Astro docs reference Jason Miller’s blog post on the idea of an Islands Architecture:

In an “islands” model, server rendering is not a bolt-on optimization aimed at improving SEO or UX. Instead, it is a fundamental part of how pages are delivered to the browser. The HTML returned in response to navigation contains a meaningful and immediately renderable representation of the content the user requested.

Rather than load an entire SPA to handle a small portion of functionality, Vue can target a much smaller section of the DOM, and render only the portion of the application that I need (in this case, a button and some JS to toggle dark mode). Vue supports this usage by default, but in the world of frameworks we tend to forget this. A number of recent episodes of Views on Vue have explored this concept, including using Vue without an SPA and building micro frontends. The Wikimedia Foundation also uses Vue this way, rendering client-side functionality on top of an existing PHP monolith (listen to my discussion with Eric Gardner to learn more).

When viewed in this way, performance is almost a byproduct of following best practices with Astro. For my personal site, I only needed a simple button to toggle dark mode. While I know this could be handled just as easily with vanilla JS, I wanted to try using Vue to build an island of functionality. Here’s my Vue component:

<template>

<button

class="dark-mode-button"

@click="toggleDarkMode"

>

{{ isDark ? "🌙" : "☀️" }}

</button>

</template>

<script lang="ts">

export default {

data() {

return {

isDark: localStorage.getItem("darkMode") === "true",

};

},

methods: {

toggleDarkMode() {

this.isDark = !this.isDark;

},

},

watch: {

isDark() {

localStorage.setItem("darkMode", this.isDark);

const html = document.querySelector("html");

if (this.isDark) {

html.classList.add("dark");

} else {

html.classList.remove("dark");

}

},

}

};

</script>And here’s an example of how I’m using the component:

---

// Import the Vue component into an Astro component

import DarkModeButton from '../components/DarkModeButton.vue'

---

<html lang="en">

<body>

... <!-- the rest of my template -->

<!-- Display the Vue component -->

<DarkModeButton client:only />

</body>

</html>Here, I’m using Astro’s client:only directive. This tells Astro that it should be hydrated on the client, so that the Javascript will be executed. In this case, because the component is accessing the window element, I want to make sure it doesn’t get executed during buildtime. The best part is that, within the Astro component, it just asks like a normal component that can accept props.

Astro has a number of renderers, and at the recent Vue Contributor Days, Fred Schott said that first-class Vue support is very important to the Astro team, and that it comes out of the box when working with Astro. You do need to add the renderer to your Astro configuration, but that’s all that is required to enable Vue components.

The Results

Rewriting my personal site took about a week. Most of my templating was migrated from Vue to Astro components (although, as noted above, this wasn’t a requirement to make the switch), with a couple Vue components for interactivity. The migration itself went very smoothly, especially since Astro support PostCSS (and therefore Tailwind) via a plugin for Snowpack. The benefits of prefetching the data and generating static HTML were obvious very early on, and the ability to mix basic HTML and CSS with Vue components was very straightforward.

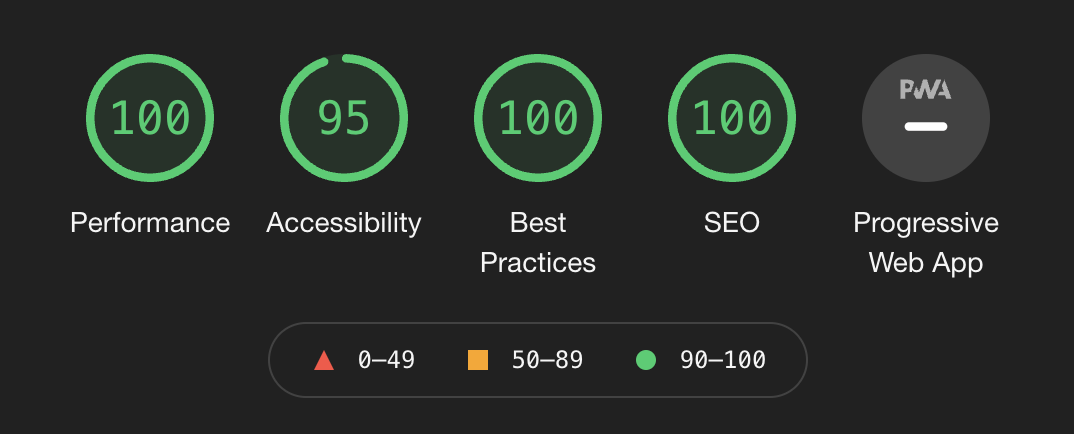

After I finished and deployed, I ran Lighthouse on the finished migration. Here are the results:

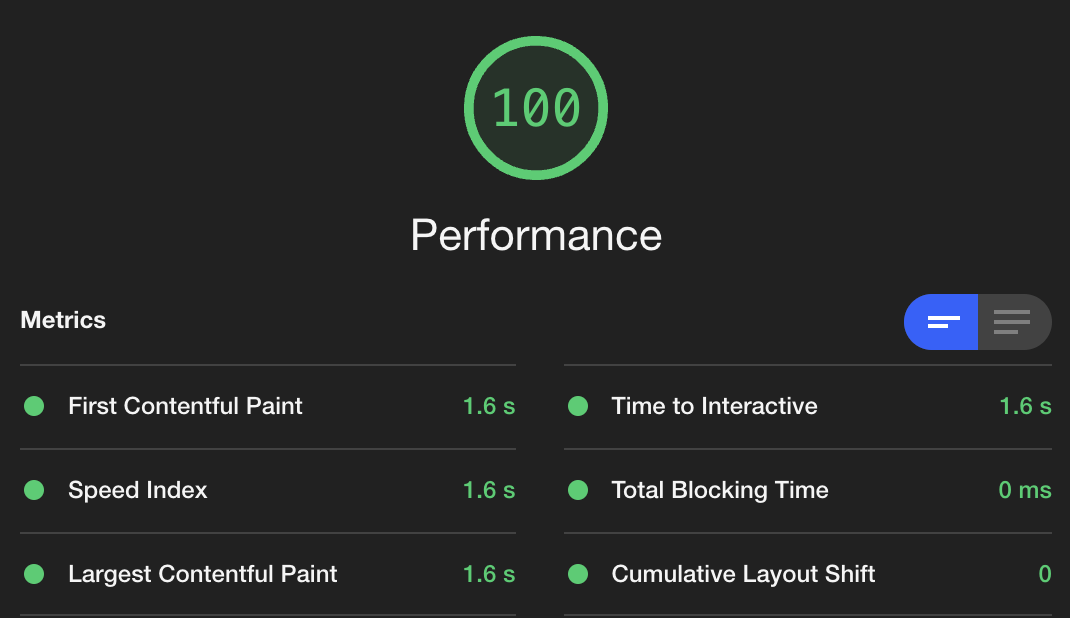

And here’s the performance results:

Much better! Because everything is being loaded as HTML and CSS, rather than utilizing a JavaScript framework to render the page, everything is much faster.

Conclusion

Astro is a relatively new tool for building static sites, but it’s already gaining a lot of traction. Astro recently won the Ecosystem Innovation Award as part of Jamstack Conf 2021. From the linked page:

This year’s ecosystem innovation award goes to Astro, an innovative Jamstack platform that lets you build faster websites with less client-side JavaScript. They make it possible for developers to build fully functional sites with any framework of their choice or none at all. Astro offers the best of both worlds when it comes to lightweight static sites generators like 11ty and bundle-heavy alternatives like Next and Svelte Kit.

I’m really excited to see where Astro goes in the future. One item on their roadmap is to include server-side rendering, which I’m very excited for personally. I look forward to seeing what else comes out of this very interesting project.

Feel free to look at the repository for this site to view the code, and compare it against the Nuxt equivalent (in the Git history). If you want to learn more about Astro, check out their site at astro.build.